It's with some trepidation that I've decided to write something about RD Laing. I don't think there's any point in trying to reconcile the wildly different opinions there are about him. As with many gifted people he had a lot of faults, and you can read all about them online and elsewhere. Having read some of his books, and quite a lot written about him, I think that what he had to say for himself is far more interesting than others' views of him.

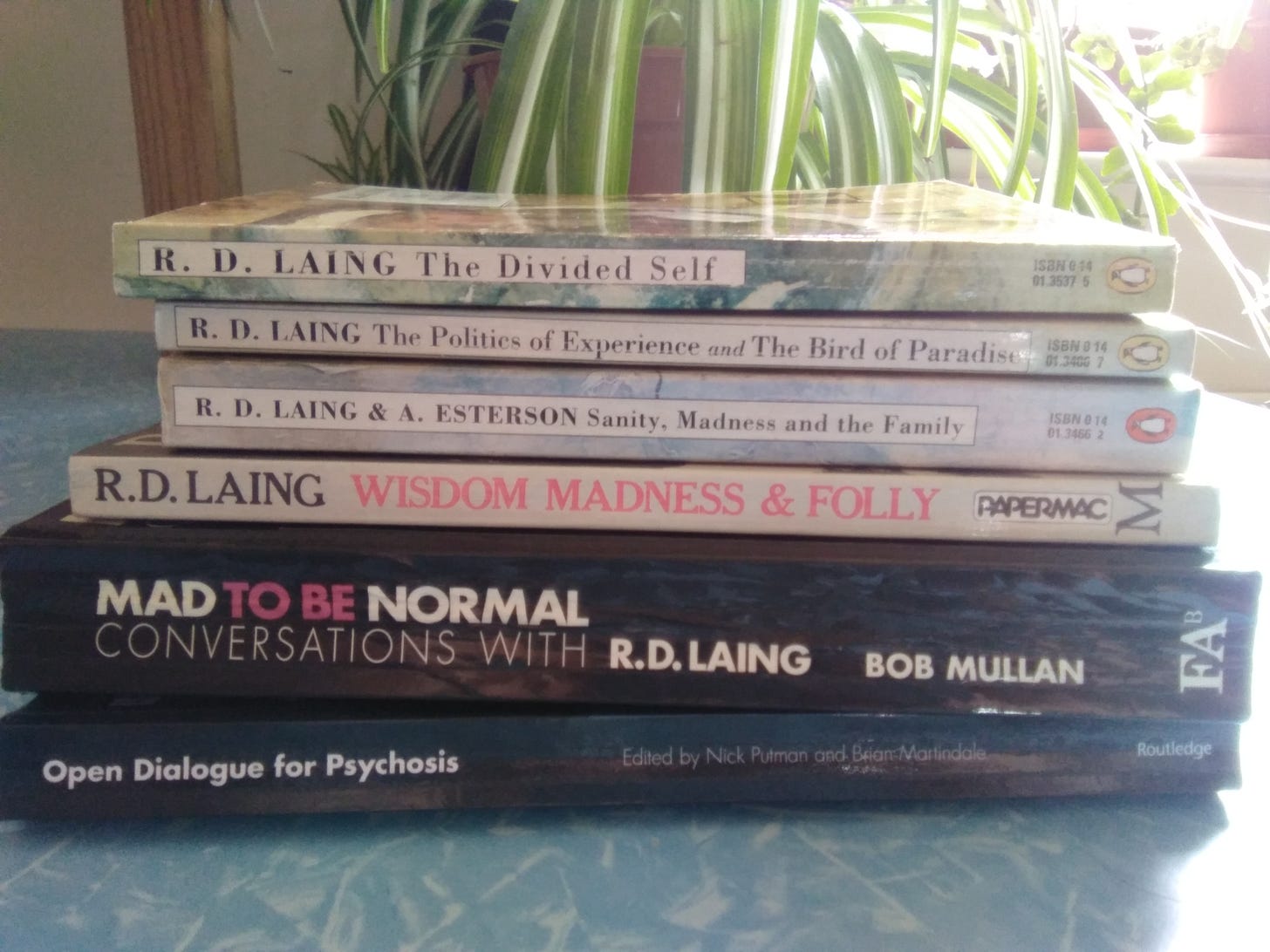

My favourite book is Mad to be Normal (1995), based on transcripts of conversations between Laing and Bob Mullan. The plan was for Mullan to write a biography of Laing, but Laing died of a heart attack in August 1989 and the biography was not written for various reasons. This is Laing talking at length, near the end of his life, about his family, influences, psychiatric career, reputation, theory and therapy, among other things.

From a young age he started reading European philosophers such as Kierkegaard, Heidegger, Husserl and Sartre. These Existential and Phenomenological writers deeply influenced him, and gave him the ability to challenge the medical approach towards psychiatric patients. In his first book The Divided Self (1960), Laing says—

“The clinical psychiatrist, wishing to be more 'scientific' or 'objective', may propose to confine himself to the 'objectively' observable behaviour of the patient before him. The simplest reply to this is that it is impossible. To see 'signs' of 'disease' is not to see neutrally … We cannot help but see the person in one way or other and place our constructions or interpretations on 'his' behaviour, as soon as we are in relationship with him.”

In his autobiography up to the age of 30, Wisdom, Madness and Folly (1986), Laing describes his experiences as a young doctor and psychiatrist in the Army, and at psychiatric hospitals in Glasgow in the 1950s. These show his compassion, and practical ideas for improving life for his patients. I'll give one example, of many. He was given permission by the superintendent and the matron to try out an experiment. Eleven of the most withdrawn female patients, who had been on the same ward for over four years, were chosen to spend six hours a day, Monday to Friday, with two nurses, in a comfortably furnished day-room. There were materials for knitting and sewing, drawing and other pastimes—

“On the first day, the eleven 'completely withdrawn' patients had to be shepherded from the ward across to the day-room. The second day, at half past eight in the morning, I had one of the most moving experiences of my life on that ward. There they all were clustered around that locked door, just waiting to get out and get over there with the two nurses and me. And they hopped and skipped and twiddled around and whatnot on their way over. So much for being 'completely withdrawn'.”

There are people today in psychiatry and mental health who are working along similar lines – Open Dialogue for instance. The book Open Dialogue for Psychosis (edited by Nick Putman and Brian Martindale) is a thorough and inspiring account of how treating psychosis as socially intelligible can produce better outcomes for patients and their families.

What would Laing think of what's going on now? I have the impression the approach to psychiatric patients is a test for how much control society would tolerate generally: deprivation of liberty, disregard for voluntary informed consent for medical treatment, and so on. With covid-19 a similar method was tried on the rest of us: deprivation of liberty with lockdowns, and pressure to get vaccinated.

I'll finish with one of my favourite quotes from Mad to be Normal. While Laing was training at the Institute of Psychoanalysis, he had four years in psychoanalysis with Charles Rycroft—

“After I had been seeing him [Rycroft] five times a week on the couch for over two years, I was going on about something that was taking place at the Tavistock – as I say he didn't make interpretations particularly but he made remarks and comments as things struck him – and he said, 'you know one of the things about when you talk, you appear to mean it'. [laughs] Sort of half joking, I said is that supposed to be some psychopathology that you are writing a paper on, 'he means what he says'. He said 'no, no. But it's very unusual'.”